The Myopia Myth

Chapter 6

THE TRUTH ABOUT MYOPIA AND HEREDITY

One of the saddest realities of contemporary eye care is that

although there are a few vision specialists with at least a

moderate interest in the cause and prevention of myopia,

most of their colleagues show not the slightest interest

in this work. They continue to claim that no one has ever

proven that acquired myopia is not inherited, and that there is

therefore no reason to believe that this problem can be prevented.

It is difficult to understand how this hereditary theory can still

persist in spite of decades of research proving the close

connection between excessive close work and myopia development.

"Heredity" does not cause myopia as many people believe. It

does, however, play a role, and it is important to understand

exactly what that role is.

Myopic parents do tend to raise myopic children, and it has

therefore often been stated that heredity is the most important

single factor in the cause of myopia. However, this tendency can

be explained in another way. In those families where the parents

are well educated and do considerable reading, the children will

normally be well educated and do much reading also. The myopia

of the children is not inherited but acquired, because they follow

the example of their parents. Heredity can be a factor to the

degree that reading ability or the desire to read is inherited, but

it is the reading, not the hereditary factor, which is the cause of

myopia. It is, however, necessary to explain why, of all the people

who do close work, not all become nearsighted, and only a

portion of these nearsighted people experience the more progressive

form of myopia. Wide variations can and do exist even among

children in the same family, growing up under similar conditions.

Ask yourself if there is a difference between these statements

about acquired myopia:

- Myopia is inherited.

- Heredity is a factor in determining who develops myopia.

At first glance, the two statements seem to say much the same

thing, but they are actually quite different. The first one is

false and the second one is true.

The latest research makes it quite clear that acquired myopia

develops from excessive accommodation. Myopia is therefore most

common in advanced, literate societies and is rare in primitive,

illiterate societies.1 This is not to say that an illiterate person

could not develop myopia. Even an illiterate person might be

spending hours each day in some form of close work requiring

excessive accommodation that could lead to the development of

myopia.

That many people have gone astray in their thinking is obvious

when one hears such statements as: "How can two children both do

a similar amount of reading and yet one develops myopia and the

other one doesn't? The cause must be heredity".

Actually, there are many possible factors, both known and

unknown, which could account for such differences, and it would be

very difficult to determine which factor is most important in any

individual case. Some of these factors are:

- The diet of the child

- The diet of the mother during the gestation period

- The distance the book is held from the eyes

- The amount of light used for reading

- How often the child looks up from the book

- How large a "cushion" of farsightedness the child is born with

- Hereditary factors

The point to be made here is that none of these factors is the

cause of acquired myopia. Generally speaking, these factors can

only influence the rate of progression of the myopia if the

environmental cause is present. If the cause is absent, virtually

no one will develop myopia. The cause, of course, is an unnatural

amount of accommodation.

Similar confusion about heredity exists when talking about

other health problems. We know that some people never get tooth

decay even though they eat an atrocious diet of refined foods, and

there are many people who foolishly say that this proves that tooth

decay is not due to faulty diet but is inherited. Yet, the simple

fact is that tooth decay would virtually disappear if we all ate a

proper diet of unrefined foods.2 Our hereditary differences would

then be of no importance because the cause would be absent.

As another example, suppose that two people are heavy smokers.

One of them dies from lung cancer at an early age and the

other lives to be 100 and dies a natural death. It is obvious that

there must be constitutional differences between the two, at least

with regard to their ability to withstand air pollution. However,

wouldn't it be foolish to attribute the early death to "heredity."

If the cause (tobacco smoke or some other environmental poison)

were not present, neither of the two would develop lung cancer.

Above were listed some of the factors that could affect the

possible development of myopia in an individual, if the cause was

present. We can list in a similar manner some of the factors that

could partially determine whether or not an individual will develop

lung cancer from smoking:

- The diet of the individual

- The diet of the mother during the gestation period

- To what extent the individual inhales the tobacco smoke

- The amount of exercise the individual gets

- Whether other health problems exist that affect the body's resistance

- Hereditary factors

The above examples are simplified, of course, but they point

out the need to stop talking about heredity as if it was a cause of

these health problems. In the absence of an obvious congenital

defect, it is incorrect to say that myopia is caused by an eye that

is too long, or a cornea that is too steep, or a lens that is too

thick. There are people who are born with long arms and people who

are born with short arms, but the arms still function properly. If

the bone is long, nature provides long arteries, veins, muscles,

nerves, and skin. Why must we continue to believe that the eye

is different and that it is a collection of parts of haphazard

sizes? By what logic can we assume that it is nature's plan that so

many of our children will find their vision failing during their

early school years? Why the widespread reluctance to accept an

unnatural visual environment as the cause? We don't have any

difficulty understanding that an unnaturally loud environment can

permanently damage our hearing. But that excessive close work can

cause myopia seems to be difficult for most people to comprehend.

Numerous researchers have found a higher incidence of myopia in

girls than in boys. Heredity need not be the reason for this. It

can be explained by the fact that boys have traditionally spent

more time in outdoor sports activities while girls have more

frequently turned to sewing, knitting and other close-work

activities.

Many birth defects have been shown to be caused by

faulty nutrition of the mother, although this fact is,

unfortunately, not as commonly known as it should be.2 It is

therefore probable that much congenital myopia falls into this

category, and that heredity plays a negligible role even in this

form of myopia. Myopic eyes can logically be considered as eyes

that are "solving" the problem of excessive close work.

Unfortunately, this results in loss of distance vision. There are

many children who are unable to solve their problem in this way.

They may find reading so tedious that they give it up; they may get

headaches; one eye may turn out or in, etc. Such people are good

candidates to become school dropouts. In fact, it has been found

that dropouts are almost never myopic. This means that either

1) they lack the ability to read and understand, or 2) they

experience vision problems, such as the above, when trying to read.

In either case, they do not read and they do not develop myopia.

It is possible that at some time in the distant future, the

course of evolution will have altered human eyes so that they can

do more close work without destroying distance vision. This might

come about by a gradual increase in the ability of the ciliary

muscle to relax itself when the distance vision starts to become

blurred. This "negative accommodation" ability is already thought

to be present in human eyes to a certain extent, and it could be

developed and strengthened through evolution.

At one time it was most common for myopia to begin to appear

in children between the ages of twelve to fifteen. This led some

investigators to believe that the myopia resulted from the changes

that occur with puberty, and that myopia was thus a delayed

response to an inherited characteristic. However, since children

are now developing myopia at a much younger age level (because

they begin their schooling earlier), we know that there is no

relation between puberty and the development of myopia.

If myopia is inherited, we would not have seen the tremendous

increase in myopia that has occurred in recent decades. Genetically

determined changes do not occur so rapidly.

At one time, most of the lenses produced by optical companies

were plus lenses to correct hyperopia or presbyopia. Minus lenses

to correct myopia made up only a small percentage of their

production. Now this situation has reversed, and far more minus

lenses than plus lenses are produced.

The age at which acquired myopia begins can vary over a wide

range - from the preschool years up to the age of forty. This fact

suggests strongly that this myopia is not inherited, since

inherited characteristics tend to occur at a relatively fixed age

for a given population and environment.

While on the topic of heredity, we should examine the question,

"Are myopes more intelligent than nonmyopes?"

Myopia and intelligence. From

time to time, reports are published showing that myopes

score higher than nonmyopes on intelligence tests and concluding

that myopes are thus more intelligent than the rest of the

population. These researchers usually go on to say that this proves

that myopia is inherited since intelligence is largely inherited.

They have even gone so far as to claim that the gene that lengthens

the eyeball also stimulates the brain. Such a statement is

indicative of the length to which some people will go to justify

their claim that myopia is inherited.

If those people who inherit a high intelligence also inherit

myopia along with it, then it should be possible to select the most

intelligent individuals from a group of primitive illiterates and

find considerable myopia in these individuals. The fact is that in

illiterate societies almost no one is myopic. Where then is this

inherited myopia? It obviously does not exist.

These researchers seem to be totally ignorant of the numerous

studies which have shown repeatedly that myopes score higher than

nonmyopes on intelligence tests because of their better reading

ability and not because they are gifted with higher intelligence.

Several papers on this subject have been written by Francis A.

Young, former Director of the Primate Research Center at Washington

State University. The following passage from one of these papers3

summarizes these studies:

Education versus intelligence:

If this consistent finding - that the proportion of

myopic persons increases with years of schooling - is

accepted and combined with the known relationship between

intelligence level and years of schooling (which parallels

that for the development of myopia), it might be

concluded that the myopic person who predominates at the

higher educational levels is also more intelligent than the

nonmyopic. It should even be possible to estimate

intelligence by determining the refractive characteristics

of the eye. Most of the studies that have attempted to

demonstrate a relationship between intelligence and

refractive error have found none, except when intelligence

was measured by written tests. There is a positive

relationship between performance on such a test and

refractive error: myopic persons tend to score higher than

nonmyopic. However, when reading ability is statistically

adjusted for, the correlation of refractive error and

intelligence approximates zero. The myopic person is a

substantially better reader than the nonmyopic.

It has thus been shown beyond doubt that myopia is not

inherited along with intelligence, but parents are still manipulated

into believing that concave glasses on their children are a status

symbol to be proud of - a sign of intelligence. They are being fed

with misinformation so that they will not be upset by their

children's myopia. Their attention is being diverted from what

should interest them - the prevention of myopia.

Reasearch by Francis Young.

Some additional work done by Francis Young needs to be mentioned

here since no book on myopia prevention would be complete

without it. Dr. Young was the director of the Primate Research

Center in Pullman, Washington for many years starting in 1957 and

has had more than eighty-five scientific papers published, many of

them on the cause of myopia. By pointing out the errors of some

earlier researchers and by systematically seeking the facts,

Young has put together an accumulation of knowledge about myopia

that is of tremendous importance. His many years of research has

produced irrefutable evidence that there is no truth

to the old belief that heredity is the cause of myopia.

However, he has yet to receive adequate recognition and praise from

the scientific community for his years of effort. Furthermore, his

work has been mostly unknown to the public.

The work that he and his colleagues have performed falls into

several categories. Some of these are: the study of the development

of myopia in monkeys; the incidence of myopia in the Eskimos of

Barrow, Alaska; and vitreous pressure measurements.

- THE STUDY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYOPIA IN MONKEYS. The word

"primate" in Primate Research Center refers to a group of animals

having similar characteristics, and to which both monkeys and

humans belong. Since certain monkeys, such as chimpanzees,

have eyes that are almost identical to human eyes, tests can be

conducted on these monkeys that would be impractical to conduct on

humans.

By using a hood to restrict the vision of monkeys so that they

could not see more than fifteen inches (38 cm) from the eye, it was

found that most of them develop myopia after a few months' time,

just as humans do.4 Monkeys living in the wild, on the other hand,

do not develop myopia.5

It was also found that the juvenile monkeys did not begin to

develop myopia as soon as the adult monkeys did under the test

conditions. However, once the myopia began to develop, it

progressed much faster in the juvenile monkeys than in the adults.

The experiments also showed that the greatest amount of myopia

developed when the level of illumination was around four

foot-candles. In other words, if the light level is less than this,

there is not enough light for the eye to focus properly and the eye

does not make the attempt to focus or exert full accommodative

effort. Once the light level rises above four foot-candles, the eye

will be able to focus and exert accommodative effort. As the light

level is increased still further, the eye needs to accommodate less

and less because the pupil becomes smaller and the periphery of the

lens is not used.

The above studies indicate that in both monkeys and humans a

ciliary spasm is of greater magnitude in the younger individuals

than in the older ones.

In order to confirm even more strongly that prolonged

accommodation was causing these myopic changes, a group of animals

was placed under the hoods for four months until they were showing

a good change into myopia. At this point, the animals were left

under the hoods but a drop of one-percent aqueous atropine was

placed in each animal's eyes every morning and evening. Atropine

is a drug that paralyzes the ciliary muscle and makes accommodation

impossible for as long as the drug treatment is continued. In

using this drug on humans it has been found that it results in a

reduction in the amount of myopia measured and a cessation in the

progress of the myopia while the treatment is continued. This was

found to be true with monkeys also. The amount of myopia was

reduced by about 0.5 diopters, and no further myopia progression

was observed.

All of the monkey studies clearly indicate that between

seventy-five and eighty percent of the animals show myopic changes,

and the remaining twenty to twenty-five percent do not. The first

stage is the development of a spasm of accommodation. Once the

spasm develops, it is followed within two to four months by an

increase in axial length. Some animals do not seem to develop this

spasm and consequently do not experience axial-length myopia.

Since those animals that do develop myopia experience fairly

high degrees of myopia (up to 7 or 8 diopters) with corresponding

axial-length increases of several millimeters, the effect of

prolonged accommodation on the development of myopia is

unmistakable.

- THE INCIDENCEOF MYOPIA IN THE ESKIMOS OF BARROW, ALASKA.

Let us turn now to another study that was made by Dr. Young and

his colleagues.6 They traveled to Barrow on the northern shore

of Alaska, where they examined the vision of the Eskimo families

living there. The Eskimo population was a unique group to study

in that the older generation was essentially illiterate and had

never gone to school, while the younger generation was required to

attend school. The older generation lived the typical outdoor

Eskimo life with little close work. This then was an opportunity to

test the hereditary or genetic theory of myopia. If the hereditary

theory was true, then there should be a similar amount of myopia in

the children and in the parents in spite of the great difference in

the amount of close work done by the two groups. Actually, just the

opposite was found.

Of 130 parents, only two showed any myopia. One had -0.25 D

and one had -1.5 D. All the rest had refractive errors

between 0 and +3 D. In other words they were somewhat

farsighted, which can be considered normal.

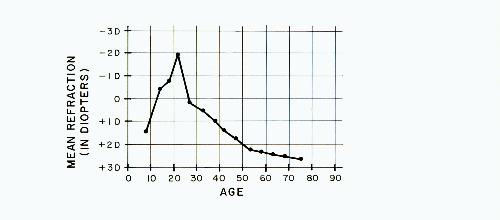

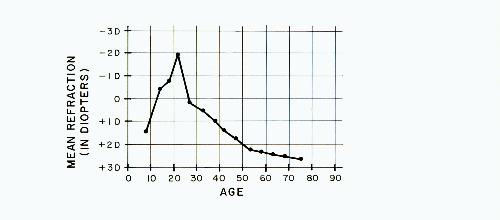

Regarding the children of these nonmyopic parents, a totally

different picture was found. Fully sixty percent of the school

children examined showed measurable amounts of myopia. Of the

fifty-three individuals who were between twenty-one and twenty-five

years old, eighty-eight percent were myopic. There was a

beginning of myopia at about age ten, with a steady increase in the

proportion of the children showing myopia up to ages twenty-one

to twenty-five years. This is shown in graph form in figure 1. It

is obvious that these myopic children did not inherit the myopia

from their parents.

Fig. 1

Furthermore, since both the parents and the children were still

using the basic Eskimo diet, at least for part of the day, these

changes cannot be explained in terms of a dietary change.

- VITREOUS PRESSURE MEASUREMENTS. In order to prove that a

pressure increase in the eye could occur in a monkey merely by

the act of accommodation, a pressure-sensitive transmitter was

developed.7 This is a small drum about the size and shape of an

aspirin tablet that contains two flat wire discs separated by an

air gap. An increase in pressure on the surface of the drum causes

the discs to move closer together. Decreases in pressure cause the

discs to move farther apart.

When an outside radio-frequency source is directed at the eye,

the signal is amplified or attenuated according to the degree of

separation between the two discs. The transmitter is surgically

placed (under anesthesia) in the vitreous chamber of monkeys.

When the monkeys have recovered from this simple procedure, it

is then possible to measure changes in vitreous pressure without

such artificial attachments as wires or needles and without the

requirement of anesthesia. It is merely necessary to restrain the

monkey's head during the measurements so that the radio-frequency

source can be brought close enough to the eye (about two or three

centimeters).

Studies with these monkeys have shown that the vitreous pressure

is least when they are focusing on a distant object and that the

pressure increases steadily as the object approaches the eye. The

maximum increase is about six millimeters of mercury above the

normal twelve millimeters of mercury. These studies thus show

that there is a direct relationship between fixation distance and

vitreous pressure.

From these and his many other studies on both humans and

monkeys, Young concluded, "It appears quite clearly that

myopia results from a continuous level of accommodation, and if one

prevents this continuous level of accommodation from occurring,

very little myopia, if any, should occur."4

The experience of numerous other researchers has also pointed

to the visual environment as the cause of myopia. For example,

members of submarine crews have become myopic due to the

confined visual space in submarines.8

Young is not the only person who has done valuable research in

myopia. There are others, and they all deserve our gratitude. The

problem is that their research is ignored by those who should be

using this new knowledge to benefit the people.

Eye disease and diet. While

this book focuses on myopia, many people suffer from eye

diseases such as cataract, glaucoma, macular degeneration and

diabetic retinopathy. While the doctors would have you believe

that this is due to heredity and that drugs and surgery

are the only answer, the true cause is faulty metabolism due

to improper diet. If you want to avoid these and other systemic

health problems, you must get your fat intake down from the usual

40% of calories to no more than 10%. This will also bring down

your cholesterol level which should ideally be under 150.

In this way you will avoid the atherosclerosis that paves the way

for these diseases. Many books on this subject may be found in your

local library. Don't fail to become knowledgeable in this area.

Don't depend on your doctor.

Cover Next